Pac Learning

This post covers Probably Approbimately Correct learning theory. The content was written in reference to course content from Henry Chai(CMU 10-401/601) and this video, Probably Approximately Correct(PAC) Learning (KTU CS467 Machine Learning Module 2).

Table of contents

Statistical Learning Theory Model

Statistically, we can precisely define our model as below:

- Data points are generated from some unknown distribution. \(x^{(n)} \sim p*(x)\)

- Labels are generated from some unknown function.

\(y^{(n)} = c*(x^{(n)})\)

- c*: target generating function

- Learning algorithm chooses the hypothsis(or classifier) with lowest tarining error rate from a specified hypotheisis(classifier) set, \(H\).

- But! Our goal is to return a hypothesis(or classifier) with low true error rate. This means we expect good generalisation.

Types of Error

Let’s review types of error we have been through.

- True error rate:

- This is the thing we ultimately care about.

- How well your hypothesis will perform on average across all possible data points.

- However, we don’t know this. Therefore, we approximate true error rate by introducing different types of error rate as below.

- Test error rate:

- Used to evaluate hypothesis performance with data set that wasn’t used to turn hyperparameters or training process.

- This is a reasonable estimate of our hypothesis’s true error.

- Validation error rate

- Used to set hypothesis hyperparameters.

- Training error rate

- Used to set model parameters.

- Very optimistic estimate of hypothesis’s true error.

- Note: in PAC learning we focus on relationship between true error rate and training error rate.

Types of Risk

Terminology alert! Although conceptuall we’re using same notion of true error rate and training error rate, we are going to use term expected risk and empirical risk in this section. Let’s think error rate as risk that your model makes mistakes.

- Expected risk of hypothesis \(h\) (true error)

\(R(h) = P_x \sim p*(c*(x) \ne h(x))\)

- Sampling over all possible data points under the distribution \(p*\).

- Empirical risk of hypothesis $h$ (training error)

\(\begin{aligned}

\hat{R}(h) & =P_{\boldsymbol{x} \sim \mathcal{D}}\left(c^*(\boldsymbol{x}) \neq h(\boldsymbol{x})\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{N} \sum_{n=1}^N \mathbb{1}\left(c^*\left(\boldsymbol{x}^{(n)}\right) \neq h\left(\boldsymbol{x}^{(n)}\right)\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{N} \sum_{n=1}^N \mathbb{1}\left(y^{(n)} \neq h\left(\boldsymbol{x}^{(n)}\right)\right)

\end{aligned}\)

- Sampling over training dataset D.

Note that \({D}=\left\lbrace\left(\boldsymbol{x}^{(n)}, y^{(n)}\right)\right\rbrace_{n=1}^N\) is the training data set and \(x \sim D\) denotes a point sampled uniformly at random from \(D\).

Our Interest

To sum up, let’s recall what our interests are when we are building a learning model. Withour a doubt, we are interested in the true function, \(c*H\). However, we have no idea what it is, so we try to approximate it. And this goal can be rewritten in format such that:

- Expected risk minimizer

\(h^*=\underset{h \in \mathcal{H}}{\operatorname{argmin}} R(h)\)

- The lowest “true” error rate

- Empirical risk minimizer

\(\hat{h}=\underset{h \in \mathcal{H}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \hat{R}(h)\)

- The lowerst “training” error rate

This observation concludes into one question: Given a hypothesis with zero/low “training error”, what can we say about its true error? Can training error give some insight about true error and true performance of our model?

Rectangle PAC1

1. PAC Criterion

\[P(|R(h)-\hat{R}(h)| \leq \varepsilon) \quad \geq \quad 1-\delta \quad \forall \quad h \in \mathcal{H}\]\(R(h)\): Empirical risk

\(\hat{R}(h)\): Expected risk

\(\varepsilon\): Difference between expected and empirical risk, upper bound error.

\(\delta\): Probability of failure.

\(1-\delta\): Confidency

\(P(|R(h)-\hat{R}(h)| \leq \varepsilon)\): Desirable property of a model

\(\varepsilon\)

Since for any set of training examples \(T \subset X\) there may be multiple hypothesis consistent with \(T\). However, the learner cannot be guaranteed to choose the one corresponding to the target concept, unless it is trained on every instance \(X\), which is unrealistic. Therefore, we don’t require L to output a zero error hypothesis - only require that error be bounded by a constant \(\varepsilon\) that can be made arbitrarily small.

\(\delta\)

Since training examples drawn at random, there must be a non-zero probability that they’ll be misleading. Therefore, we don’t want L to succeed for every randomly drawn sequence of training examples - only require that it’s probability of failure be bounded by a constant \(\delta\) that can also be made arbitrarily small.

2. PAC Learning Model: General Setting

- \(x\): Set of all possible instances over which target functions are to be defined.

- \(C\): Set of target concepts the learner may be asked to learn. Where each \(c \in C\), \(C\) may be viewed as a boolean-valued function \(c:x \rightarrow {0, 1}\). If \(x\) is a positive example \(C(x)=1\); If \(x\) is a negative example \(C(x)=0\).

- \(D\): Examples are drawn at random from \(x\) according to a probability distribution \(D\).

- \(H\): A learner \(L\) considers a set of hypothesis \(H\) and after observing some sequence of training examples, outputs a hypothesis \(h \in H\) which is its estimate of \(C\).

- The true error of hypothesis \(h\) (denoted \(\operatorname{error}_D(h)\)) w.r.t. target concept \(c\) and distribution \(D\) is the probability that \(h\) will misclassify an instance drawn at random according to \(D\).

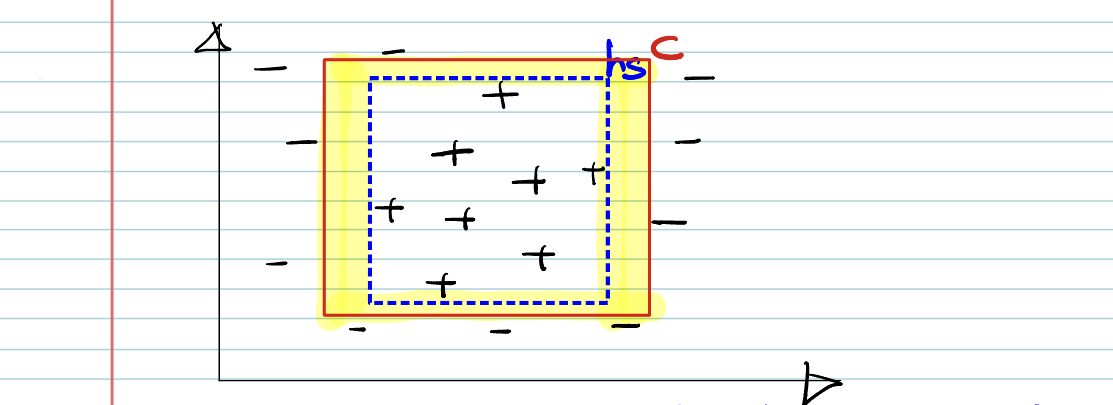

3. Rectangle PAC Learning

- Our goal is to find the best \(h\), that approximate target function \(c\).

- \(c\): Real target function

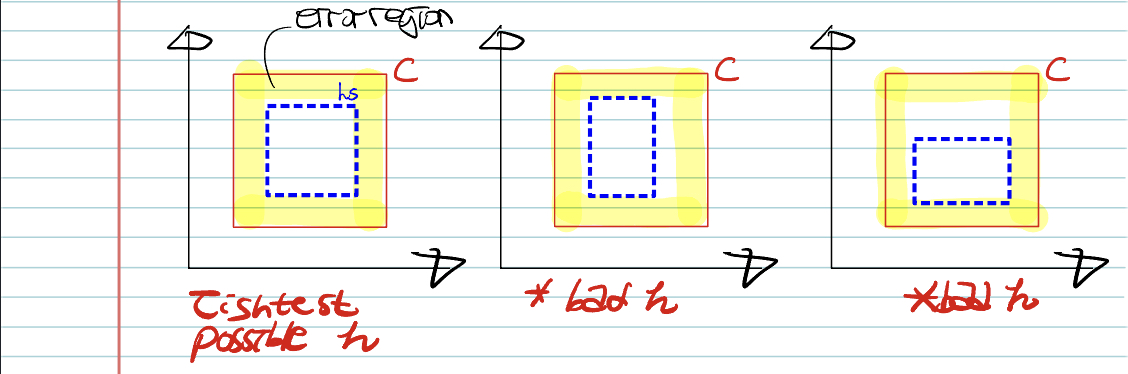

- \(h_s\): The tightest possible rectangle around a set of positive training example.

- Since \(h_s \subset c\), error region = \(c-h\).

- To be approximately correct, the area of error region should be bounded by \(\varepsilon\).

Idea: If at least one of the side was misclassified, all the samples of training set, we’ll get bad hypothesis.

- Error region = Sum of four rectangular strips < \(\varepsilon\).

- Each strip is at most \(\varepsilon / 4\)

- Probability of a positive example falling in any of the strip(error region) = \(\varepsilon / 4\)

- Probability that a radomly drawn positive example misses a strip = \(1-\varepsilon / 4\)

- Probability of \(m\) examples miss a strip = \((1-\varepsilon / 4)^m\)

- Probability of \(m\) examples miss any one of strip \(<4(1-\varepsilon / 4)^m\)

To solve PAC learning,

\[\begin{aligned} & 4\left( 1-\varepsilon /4\right) ^{m} <\delta \quad \text{[Hypothesis PAC]} \\ & \text{Using inequality,} \; 1-x \leq e^{-x} \quad \text{[x = $\varepsilon$ / 4]} \\ & 4\left( 1-\varepsilon /4\right) ^{m}\leq 4e^{-m\varepsilon /4} <\delta \\ & m >\dfrac{4}{\varepsilon }\ln \dfrac{4}{\delta } \end{aligned}\]4. Conclusion

If we ant to have an accuract of \(\varepsilon\) and confidence of at least \(1-\delta\), we have to choose a sample size \(m\) s.t

\[m >\dfrac{4}{\varepsilon }\ln \dfrac{4}{\delta }\]-

Content and explanation originally from this video, SanITtips ↩